Creativity

Tools shape how we do creative work. AI tools need good constraints, high sensitivity and an understanding of remixing to make them easier to wield in the search for great ideas.

I want to empower creative people to do the best work of their lives. Whether it’s making music, writing code, or building businesses, we need more people in the arena. New tools have consistently expanded what’s possible—and who can create—and AI is no different. The tools we use shape what ideas we can imagine. AI, in particular, has the potential to expand creative possibilities in ways we haven't yet fully realized. Like a Y-Combinator,1 creatives will build tools that make more creatives.

Lately, I’ve been exploring these ideas as a member of South Park Commons, a community that embraces creativity's messy, nonlinear journey. It’s a fitting place to develop and refine these ideas.

The job of a creative

Someone doing creative work is exploring a unique part of the territory of “all possible ideas” to uncover good ideas that are meaningful and moving. The territory of all possible ideas is incalculably large. To narrow that down, creatives craft a sense of taste to separate good from bad. Actors develop a taste for what pose to strike; videographers discover what angle to shoot; editors adjust the color profile to evoke emotional responses from their audience. Similarly, SaaS entrepreneurs learn the right questions to ask working professionals to understand if there’s a business there before writing a bunch of code.

Individual creatives are at the vanguard, prospecting for new good ideas surrounded by a heavy fog of war. Each one contributes to our collective understanding of the explored territory and shared sense of taste.2

The job of tools

Creatives don’t start with perfect ideas. Their concepts are shaped by the tools they use, which guide the process and instill a sense of taste. For example, smartphone cameras make it easier for users to follow the rule of thirds to capture meaningful moments more evocatively. Web frameworks guide software engineers by breaking problems down into the right conceptual parts. Tools influence how we think, and better tools lead to better ideas.

When I talk about tools, I mean more than just wrenches and pens—I’m also talking about the tools that shape our society, like the alphabet3 and capitalism. These tools can remain stable for centuries until a new idea changes our understanding of the world. Large language models and generative AI are shaping up to be excellent tools for manifesting new ideas. Far from the sci-fi predictions of cold, calculating robots, they’re densely encoded with our human sense of taste. To fully realize their potential, we’ll need to combine that with what we already know about building great tools.

The shape of good tools

Good tools help us have better ideas. The better our tool ideas, the better our tools will be. The better our tool-making tools, the better our tool ideas will be. It’s all helplessly meta.

Good constraints

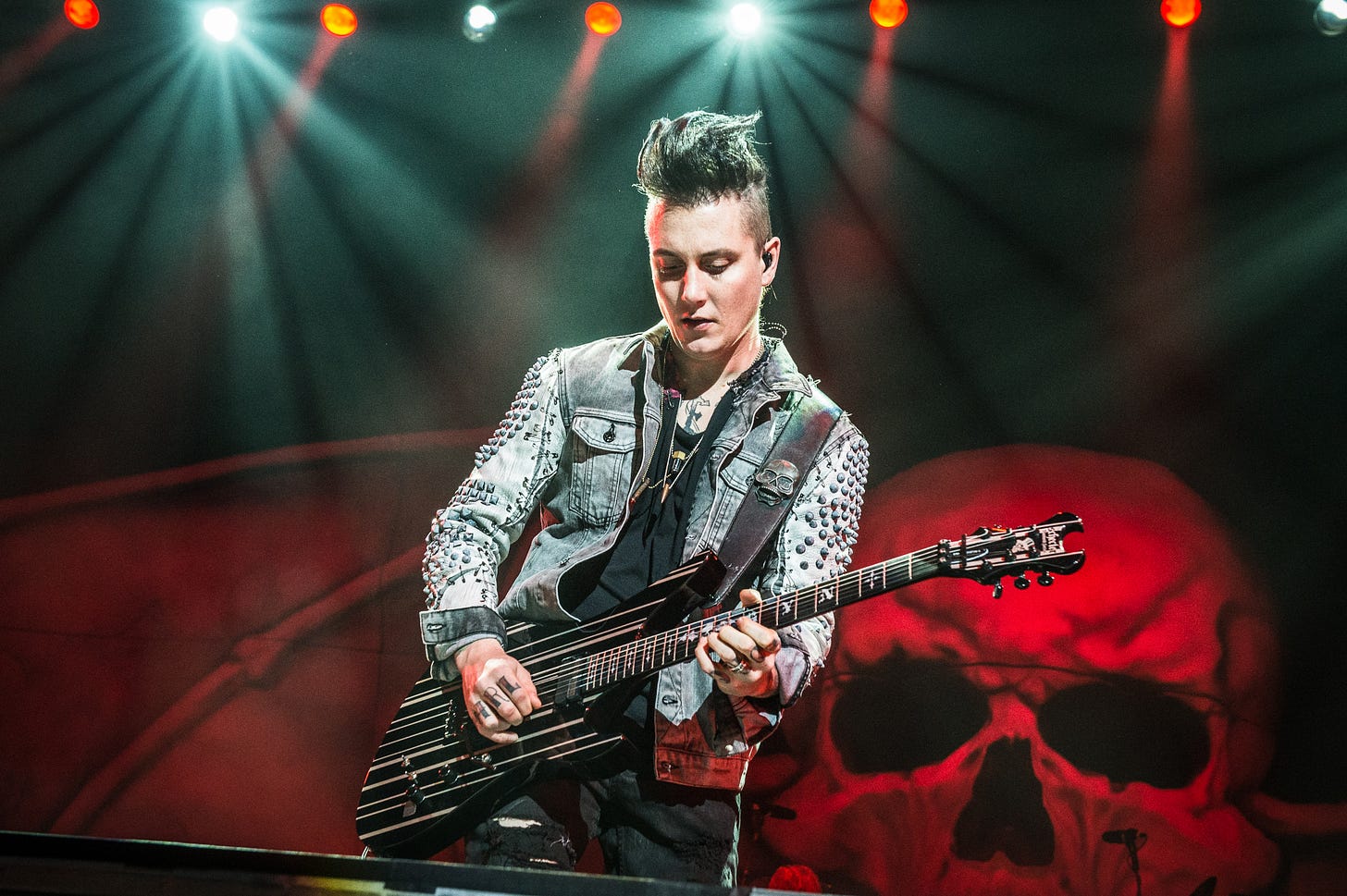

Constraints limit what can be expressed through a tool. The proper constraints limit in ways that lead to good ideas. The set of all possible musical notes is much smaller than the audible frequencies. Plenty of pleasant sounds are excluded, but the trade-off is worthwhile because it makes it harder to make a mistake. Even more constraining frameworks of scales and chords make it easier still.

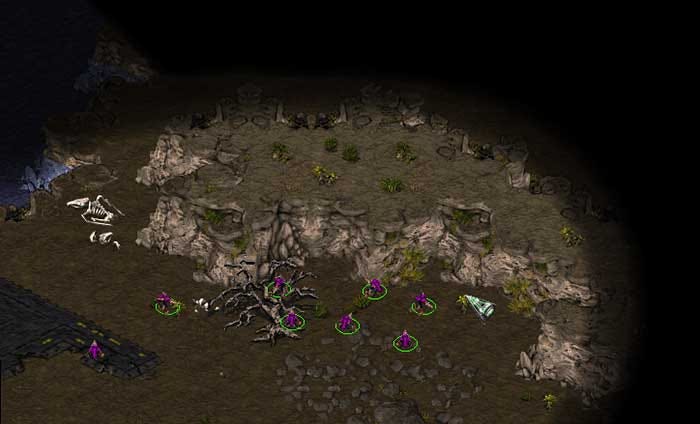

There’s a reason more songs have been written for the guitar than the violin over the last 100 years. Violins require more training and focus because their continuous necks can play frequencies between notes. In contrast, guitar frets provide clear boundaries, helping musicians focus on other parts of the creative process. Today’s AI tools are still too nascent to effectively guide creatives toward good ideas. They look more like violins than guitars, but they are still discovering their metaphorical frets to help creatives stay within their strengths.

Bad constraints don’t limit ideas enough or in ways orthogonal to finding good ideas. The ‘Innovators Dilemma’ describes Kodak's failure to adopt digital film because they constrained themselves to ideas that wouldn’t cannibalize their existing film products. Unfortunately for them, the transition to digital was inevitable, and startups who did not have the same constraints took the market.

Peak under the hood

Tools should run well in a default setting, but sometimes, creatives must challenge constraints to find an unexplored patch of new good ideas. Good tools let creatives peek under the hood and modify the internals.

Constraints are fractal, so tool makers must choose how to allow creatives to peak under deeper and deeper hoods progressively. Accounting for every constraint is impossible, but good tools prioritize well. Guitar tuning is reasonably standardized to EADGBe, but playing other tunings is more common than defining new notes. In line with those values, re-tuning a guitar is more straightforward than rearranging the frets, and changing the volume is more frequent and easier than re-tuning an electric guitar. On the other hand, if your search for good music makes you question whether strings are the best source of vibration, a guitar won’t cut it. You’ll have to try another instrument.

AI tools are so nascent that they’re not exposing very many knobs to creatives. Creatives might need to see the underlying prompts sent language models to discover better ones, even when you provide sensible defaults. That’s how we move from a local maxima closer to the global maxima. It’s tempting to hide these as trade secrets, but that will only limit more effective creatives.

High sensitivity

Good tools are highly sensitive, so creatives can wield them as an extension of themselves. As Bret Victor describes in this fantastic talk, creatives model their movements in their brains. The less feedback they get, the more they have to model internally. There’s a limit to how much our brains can model. While Michael Jackson’s voice and training allowed him to model whole songs in his head and express them to studio musicians, most of us will write better songs with Garage Band.

Each brush stroke teaches us how to paint. It would be incredibly limiting if painters wore blindfolds until their works were entirely done. Yet, that’s how many software engineers write code and how we all took photographs before polaroids or digital film.

Struggle

Some argue that new tools make art 'too easy' by removing struggle, implying a lack of value. But this view is too narrow, elevating only certain kinds of familiar struggle.

Painters who mix their paints struggle differently than painters who use the color picker in Photoshop. In both cases, the experience is highly sensitive and deterministic. Over time, both painters will get the color they want by modeling the results in their heads and building intuition. Mixing paint takes longer and is more challenging to model, so those artists spend relatively more time on that part of the work. Photoshop artists will instead struggle differently, trying many more strokes and colors because their choice is more reversible. Better tools change what creatives struggle with but don’t eliminate the struggle altogether. Struggle is an emergent property of doing creative work.

Good struggle is playful experimentation in the unknown, while bad struggle is the hurdles to executing well-known ideas. Bad struggle comes from inefficient tools or unnecessary constraints that waste creative energy, leaving us bogged down in details instead of exploring the unknown.

AI tools often introduce slow feedback loops, where entire works are generated and must be remade with each revision. This randomness creates bad struggle by forcing creatives to rely on chance rather than building reliable strategies for consistent results.

[it] feels like the computer is telling my brain This Is What You Should Have Said, rather than letting my brain come up with the words. and then it doesn't sound like me. it sounds like a weird little simulacrum of [me] - Isabel Kim

Critics like Isabel Kim argue that AI-generated text tells her what to say rather than allowing her to find her voice. This is the wrong kind of struggle.

Tools are slowly getting more sensitive to nuanced changes with less entropy, creating tighter feedback loops so artists can model less in their heads. A straightforward way to do that is literally making AI models faster. You can try out Flux tuned for speed on replicate. It’s quick enough to generate images as you type, which gives way more information per keystroke. Masking and fine-tuning similarly allow for finer revision.

Understandably, some creatives view technology as competition. If the sense of taste they’ve built within themselves is now well encoded into a piece of software, then the struggle they earn a living with is now the bad kind. In Hidden Figures, Katherine Goble helped her team transition to NASA’s digital era, but not everyone adapts so easily. Failing to adapt can have real consequences for a creative’s livelihood. This might be so disruptive that we question economic ideas like capitalism itself.

Everything is a Remix

"Everything is a remix" is a well-established idea, and I stand on the shoulders of the giants who discovered it. At their core, good ideas often come from combining old ones in new ways. This is true when VCs ask startup founders, “Why now?” directors adapt books into movies, or engineers “rewrite it in Rust.”

Good tools help creatives connect seemingly unrelated ideas and guide them to combinations worth pursuing. Some tools reduce the energy required to refine ideas, while others introduce well-targeted entropy to identify which ideas deserve attention.

Critics claim AI can't generate original ideas, but that's shortsighted. AI tools see the world in a different way. They uncover novel connections humans might miss and experiment on a scale far faster than we can manage. There will be more moments like Alpha Go’s ‘Move 37’, which changed how people thought about Go forever.

Creatives will eventually use AI-encoded taste to determine which remixes have potential. For example, a movie exec might model their audience to understand if a pitch will appeal to enough people to warrant production. TikTok succeeded by replacing user-curated networks with an algorithm, and similarly, AI will guide content producers toward commercially viable ideas or potential Academy Award winners. While human attention may always be valuable, I’m not sure there’s any part of the creative remixing process that will remain solely the domain of humans.

Closing thoughts

AI will evolve like past technologies—by automating aspects of the creative process and amplifying human potential. Rather than eliminating creative struggle, these new tools will refine the challenges we face, empowering creators to take on more complex projects and push further boundaries. I hope this understanding of constraints, sensitivity, struggle, and remixing clarifies the path to get there.

Yes, that Y-Combinator, too: The Y combinator is … a program that runs programs; we're a company that helps start companies.

This is true of mundane things, too! Someone who develops an efficient way to make cardboard boxes explores that territory so that others don’t have to. If they do a good enough job, we can stop looking in that region and spend our limited time elsewhere.

See: writing is thinking.

Great article. Couple thoughts:

* The guitar and violin analogy works well for me

* “AI tools are so nascent that they’re not exposing very many knobs to creatives” - part of me wonders whether that’s even possible. I’ve read Wolfram’s paper on ChatGPT, and I could see _him_ be in awe/wonder about the technology behind LLMs. The innards seem so fuzzy and non-deterministic to me.

* “Struggle is an emergent property of doing creative work.” - it rings true and yet something about this statement bothers me. I think it’s because I’ve spent all of my career on helping non-creatives move faster, so anything else screams inefficiency to me. But that’s not true here, I respect that.

* You used music a lot as examples in this piece - I wonder if writing could have been included as well.

I like the quote in this article https://www.geoffreylitt.com/2023/03/25/llm-end-user-programming.html

"Chat will never feel like driving a car, no matter how good the bot is". As you identified the input space is too big.